To my great love; Mazdak

Pirayeh Yaghmaii

“For all the messengers who came before me did not write down their wisdom as I have written mine.

They did not adorn their wisdom with illustrations as I have adorned mine.

I have brought this from the heavens as a sign of my prophethood.”

Mani (1)

Most researchers, translators, and writers know Mani solely as the founder of Manichaeism and, so to speak, a prophet. However, the term “prophet” is far too limited for him, because Mani was much more than that. Mani was a masterful painter, an unparalleled calligrapher, an extraordinary poet, a highly esteemed physician with unbelievable supernatural powers, and, most importantly, a human being.

A human who, with his lofty worldview and his astonishing love for the existence of humans, the existence of animals, and the existence of all living beings, sought the salvation of the human soul and its liberation from inner darkness. And in this path, he utilized all of his artistic skills—painting, calligraphy, poetry, oration, and even his medical knowledge—to guide humanity toward the realm of light.

Undoubtedly, a human with such vast and profound dimensions—unprecedented in any of the prophets who came before him—could not simply be an ordinary prophet confined to delivering conventional religious messages and rigid moral doctrines.

Mani’s influence on the world is so immense and far-reaching that even after many years, people remain curious about his philosophical life in their quest for salvation and artistic inspiration. For this reason, it is entirely fitting that he ranks 83rd on Michael H. Hart’s list of the 100 most influential figures. (2)

Biography of Mani:

Mani, the Iranian prophet and founder of the religion of Manichaeism or the “Religion of Light,” was born at the beginning of the 3rd century CE (AD) on April 14, 216 AD, in a place near Ctesiphon, in the province of Asuristan, in the village of Mardinu, east of Babylon—which was then part of the Sassanian Empire. Mani himself refers to his birth in a poem as follows:

“I have risen from the land of Babylon to spread the call of my mission far

and wide.” (3)

But unfortunately, some scholars and poets, including “Ferdowsi”, the author of the “Shahnameh” consider Mani to be a Chinese painter and say that he came from China to the court of the Iranian king “Shapur”. (4)

There is no precise information available regarding Mani’s original name. Dr. Jaleh Amouzgar, a professor of ancient Iranian languages, posits that the etymology of the name ‘Mani’ is rooted in Aramaic, and in Persian texts, it has been interpreted as the ‘Prophet of Light.’ (5)

Professor Mary Boyce also shares this belief. (6)

However, the book ” Ginza Rabba / Ginza Rba ” (7) derives the word “Mani” from the word “Manda”, meaning “mysticism,” “wisdom,” and “soul,” and states that it shares roots with words such as “Mana” and “Mankia.” (8)

In Roman and Greek sources, the name of Mani has been recorded as ‘Manichaeus’ and ‘Copricus.’ In Latin Christian sources, it is written as ‘Corbicius.’ (9)

The name of Mani’s father has been recorded in various forms, such as “Pātak,” “Fātak,” “Fāteh,” “Pātig,” and so on. For instance, Muhammad Shahrastani (6th century AH) (10) mentions it as “Fātak,” while Ibn al-Nadim records it as “Fattāq Bābak.” (11)

In any case, Mani’s father was from Hamadan and belonged to the affluent class. Mani’s mother, named “Maryam,” was from the Kamsarakan family and was connected to the Parthian dynasty. (12)

When Mani was born, his father, “Fātak,” was in Ctesiphon. According to tradition, he had joined the religious sect of the “Mughtasila” (Baptists) after receiving a divine revelation in a temple. (13)

The Mughtasila were a white-robed sect who followed a Mandaean-Gnostic tradition and believed that the ritual washing of the body was a means of salvation. (14)

From the age of six, Mani joined his father and, under his guidance, became a follower of the Mughtasila (Baptist) and Gnostic traditions.

At that time, in Mesopotamia—which was part of the Iranian Empire—various religions were freely active.

Among them were Zoroastrianism, Buddhism, and Gnosticism, as well as Christians who had fled there to escape persecution in Rome and were spreading Christianity. Thus, Mani lived, learned, and grew up in such an environment. (15)

Mani, at the age of twelve, realized that there was a supernatural force within him that inspired him, and he named it “Toom (his twin spirit)” or “Nerjemig” (16).

(This divine twin in Christian writings is referred to as the Paraclete (17).

In the book ‘Al-Fihrist’, the description of the inspiration of ” Toom to the twelve-year-old Mani is as follows:

“Forget this community (i.e., the baptizers), for you do not belong to them. Your primary duty is to guide others toward ethical principles and to abstain from lusts and worldly affairs. But However, since you are still a youth, the time has not yet come for you to rise openly.” (18)

From then on, Mani began to study religions and faiths seriously and comprehensively. And since he was an exceptionally talented child with extraordinary intelligence, he became curious about these religions. He considered the differences and compared them in his mind.

At the age of 24, that inner force, Taum once again inspired him, revealing that the time had now come to proclaim his mission. With this call, Mani arose to his prophetic mission.

He broke away from the baptizers’ sect and separated from its mystical leader, ‘Al-Khasai’ And one of his reasons was: “The purification that Jesus speaks of is achieved through knowledge and mysticism, and it cannot be attained merely through physical washing.” And in this way, he emphasized the purity and cleansing of the soul, prioritizing it over the purity and cleansing of the body. (19)

After that, he explained his teachings to his father and close relatives, inviting them to join his faith. Moreover, being a skilled orator, he delivered captivating speeches in Babylon and Mesopotamia, which deeply influenced many and he gained many followers.” (20)

Mircea Eliade believes that the beginning of Manichaeism can be traced back to the second revelation that came to Mani at the age of twenty-four, specifically on April 12, 240 AD. (21)

Among Mani’s followers was a sailor who was about to embark on a journey, and Mani joined him for his first missionary voyage. (22) Most scholars believe that Mani traveled by ship to “Hind” (modern-day India). However, this is not accurate. The land Mani traveled to, which is mistakenly referred to as “Hind,” is actually “Hindijan” or “Hindigan”, a historical region of Iran that is still known today and is located in southern Khuzestan. (23)

From Hindijan, Mani traveled toward Turan and Mukran (modern-day Balochistan and Sindh). During this journey, he succeeded in converting the king of Turan and a group of his companions—who were Buddhists—to his faith, which was considered a significant victory for him. (24)

On the other hand, at that time, the Sassanian Empire had expanded as far as central India, and many Indians who were Buddhists lived along the shores of the Persian Gulf and in those regions. In some areas, their numbers were so large that they even built temples for themselves. (25) Mani, while living among them, became acquainted with Buddhism, adopted certain aspects of it, and integrated them into Manichaeism.

After this, Mani returned to Pars (Persia) and traveled on foot through the region. Although he faced much hardship, there were also significant successes. One such success was his meeting with Peroz, the brother of King Shapur , who supported Mani personally as well as his faith and arranged for him to meet the king. (26)

According to Ibn al-Nadim, on Sunday, the first day of the month of Nisan (when the sun was in the constellation of Aries, corresponding to March 20, 242 AD), which was the day of Shapur’s coronation, Mani, along with two of his close companions, was granted an audience with Shapur.

This meeting was highly significant, as when Mani appeared before Shapur, the king saw a radiant light of sanctity emanating from Mani’s shoulders, which deeply impressed him. As a result, Shapur accepted all of Mani’s requests. (27)

Mary Boyce writes about this:

“As they say, some time later, Mani appeared before Shapur and placed a crown on his head, and on his shoulders (Mani’s shoulders) there were lights like blazing torches. Thus,he was called the Angel of Light.” (28)

It was at this very coronation ceremony that Mani, who had been tasked by the scholars to congratulate Shapur, took the opportunity to explain his religion with eloquent and captivating speech. He asked Shapur to honor his followers so that they could freely travel and preach wherever they wished. Shapur granted Mani this permission and even considered replacing Zoroastrianism with Mani’s religion as the official state religion.

The reasons for Shapur’s support of Mani were twofold. First, unlike his father, Shapur was not strict in religious matters. Second, Shapur was focused on expanding his empire, and since Mani’s religion was a synthesis of several faiths and had the potential to encompass many regions, Shapur saw it as suitable for his goals.

According to Coptic-language Manichaean writings, Mani enjoyed Shapur’s protection for many years and even accompanied him during the Battle of Edessa (a war between Iran and Rome, between Shapur and Valerian). During this time, Mani engaged in extensive activities to spread his religion, sending intelligent representatives and envoys in all directions. In gratitude for Shapur’s support, Mani dedicated his book Shabuhragan to him.

However, although Shapur held a favorable view of Mani in every respect and supported him, he never officially adopted Mani’s religion as the official religion. (29)

However, it can be said that Shapur, envisioning a larger empire that included Christians, Buddhists, and Zoroastrians, had specific goals regarding Mani’s religion. (30)

The End of Mani’s Life

After Shapur’s death in 273 CE, his son “Hormuz I” succeeded him. He also adopted a peaceful approach toward Mani and his followers, but he passed away after a year, and Shapur’s second son, “Bahram”, became king.

Bahram, incited by the Zoroastrian priests—especially Kartir (31)—held an unfavorable view of Mani. Therefore, during the latter part of his reign, when Mani was preparing to travel to Khorasan, Bahram compelled the state officials to prevent his journey. Mani was forced to return to Ctesiphon, and then he was summoned to appear before Bahram. (32)

The account of the cold reception and meeting between Bahram and Mani was recorded by Nuhzadag, one of Mani’s companions who remained with him until the final moments, in the book Manichaean Homilies ( the Manichaean texts written in Coptic)

He described it as follows:

Mani arrived (in the presence of King Bahram I). The king was in the midst of a meal (= he was eating) and he had not yet washed his hands (= he had not yet finished his meal).

The servants entered and announced that Mani had come and was standing at the door. The king sent a message to Mani, saying, “Wait for a while until I come to you myself.

Mani sat near the guard until the king washed his hands (= finished his meal) and rose from the table, as he intended to go hunting. Then, he approached Mani and said to him:

You are not welcome!

Mani replied :What wrong have I done?

Bahram said: I have sworn not to allow you to enter this land.

Then, aggressively, he said to Mani:

Alas! What are you worthy of? What are you fit for? You neither go to war nor hunt. Perhaps you are suited for medicine and healing, but you do not even do that.

Mani replied: I have done no evil to you, for I have always done good to you and to your family. I have been a devoted servant to you, removing demons and lies from them. Many were those I saved from illness, many were those I relieved from years of fever and chills, and many were those who came to death’s door, and I brought them back to life.’ (33)

After Bahram treated Mani with insolence, he ordered him to be thrown into prison and put in chains (34).

Following a show trial orchestrated and conspired by Kartir, Mani was accused of persuading a prince to change his religion, and thus, he was sentenced to death. (35)

Based on what Tha’ālibī narrates about this show trial, a conversation between Kartir and Mani took place in the presence of Bahram as follows:

The mobad (Kartir) asked Mani : Is destruction better or construction? Mani replied : The destruction of the body leads to the prosperity of souls.

The mobad said:Tell us, is killing you construction or destruction?

Mani said:This is the destruction of the body.

The mobad said: Then it is fitting that we kill you, so that your body may be destroyed and your soul may be constructed! (36)

The Death of Mani

Arthur Christensen says:

The death of Mani has been described differently in various sources. According to one Eastern account, Mani was crucified—while still alive, his skin was flayed, his head was cut off, and his skin was stuffed with straw. It was then hung on one of the gates of the city of Gondishapur in Khuzestan, which thereafter became known as the Gate of Mani. (37)

In the book ” al-Athār al-Bāqiya” by Abu Rayhan al-Biruni, it is mentioned that Mani had a book in which he foretold his own death. It is said that Mani claimed he was within the existence of the Satanic king and promised to heal the king (meaning Satan would destroy him). However, he was unable to fulfill his promise. As a result, the king ordered his hands and feet to be bound, and he was sent to prison, where he died. After his death, his head was severed from his body and hung at the gate of the royal court, while his body was thrown into a public passageway. (38)

Some other sources claim that Mani was captured on Wednesday, the 8th of Shahrivar in the Yazdgirdi calendar, and was thrown into prison. At that time, he was in his late 59s, and after 26 days in prison, he died at the age of 60. After his death, his body was hung (for displayed publicly).

The burial place of Mani is located in the same spot known as the Tomb of Daniel and In recent years, it has been speculated that the ancient city of “Shush” (City in Iran) was in this vicinity. (39)

The website ” Wiktionary” also, under the entry “Khuzestan,” contains a portion of a Parthian text on a Manichaean manuscript that speaks of the time and place of Mani’s death. This manuscript dates back to the 3rd century AD (i.e., three hundred years before Islam). The transliteration of this text into Persian is as follows:

“Four days past the month of Shahrivar, on the day of Shahrivar, a Monday, at eleven o’clock, in the province of Khuzestan, in the city of

Bit Lapat [which is the same as Gondishapur], the Father of Light [i.e., Mani] ascended.” (40)

Ferdowsi, in the Shahnameh, attributes Mani’s death to the era of Shapur, which does not align with historical records. Based on the Eastern narrative, Ferdowsi includes verses in the Shahnameh stating that Mani was skinned alive, Then his head was cut off, and his skin was stuffed with straw and hung on one of the gates of the city of Gondishapur in Khuzestan. (41)

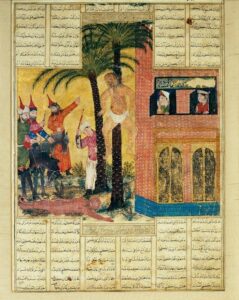

According to these verses of Ferdowsi, an illustration has also been included in the Shahnameh of Abu Sa’idi, which is the only existing depiction of Mani’s death in Iran.

This illustration, along with its related descriptions, is attached.

In the center of this image, there are two palm trees, which are characteristic of tropical regions. This indicates that the painter intended to allude to the geographical location of the event as well, because it is narrated that this incident took place in the city of Gondishapur in Khuzestan—one of the hottest cities in Iran.

In this image, Mani, who is the main subject, is depicted as split into two. One figure of Mani, wearing a shawl around his waist, is hanging from one of the trees by a rope. According to the narrative, this figure represents his flayed skin, which has been stuffed with straw.

Another figure, which represents his body, lies naked on the ground.

The limbs and face of this figure are indistinct and depicted in a dark red color.

On the left side of the painting, four men are depicted: two are on horseback, and the other two are on foot.

The man riding the horse, dressed in distinctive and almost aristocratic clothing—colored green—is a Zoroastrian priest (mobed). He is holding something resembling a small staff or whip and is pointing it at the corpse, demonstrating his power.

The standing man dressed in red, pointing toward the top of the tree with his hand, is a soldier. He is in the process of reporting to the man on horseback

The man standing next to the tree is striking the corpse of Mani, which lies on the ground, with a stick.

On the right side of the image, a brick building with two arched doors is visible. According to the story, this structure is a hospital.

Above this building, there are two windows. Through the windows, two women are seen looking at the corpse of Mani, which is hanging from the tree. One of them has her finger raised to her mouth in astonishment.

Above the windows, there are decorative inscriptions, likely in Kufic script, made of turquoise tiles. Unfortunately, due to the deterioration of the image, they are no longer legible.

A row of blue tiles is also visible at the base of the building. Overall, the image showcases architectural features characteristic of the Sassanian period.

The verses present in this painting are from Ferdowsi’s Shahnameh, and Ferdowsi has described the event of Mani’s death with a sense of satisfaction. (42)

Footnotes:

- Mani: The Painter Prophet, The Last Prophet?

A conversation with Professor Touraj Daryaee, a professor of Iranian history at the University of California, Irvine, on the “Ofogh” program from the Voice of America news network about Mani.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NmIR5IzZk402. Michael H. Hart

http://arankingofthe100.blogspot.com.au/2011/09/michael-h-hart.html3. Abolghasem Esmailpour Motlagh/The Myth of Creation in Manichaeism/Fekr-e Rouz Publications, First Edition, Tehran, 1996, p. 13.

And also:

Boyce, Prof Mary/Mani’s spirit and matter/ April 7, 2006

Mani was born on 14 April, A.C. 216, in northern Babylonia, which then formed part of the province of Asoristan, in the Parthian empire. http://iranian.com/History/2006/April/Mani/index.html4. Ganjoor website, section on the reign of Shapur:

A man, an eloquent speaker, came from China, A painter whose like the world had never seen/ He was highly skilled and his name was Mani.

Ferdowsi, in these verses and the lines that follow, portrays Mani as a painter and deceiver causing Shapur to doubt his teachings and ultimately leading to his execution./ The discrepancies in the Shahnameh with historical realities are greatly detrimental to the knowledge of Iranians who believe in Ferdowsi, as well as to the art of Persian miniature painting.

It must be said that even now, a great number of people still consider Mani to be Chinese and regard Persian miniature painting as Chinese.

http://ganjoor.net/ferdousi/shahname/zolaktaf/sh15

5, Jaleh Amouzgar / “Our most significant source of information about ‘Mani’ has been his opponents.” / Farhang-e Emrouz Website.

http://farhangemrooz.com/print/27491

- Mani’s own name, a fairly common one, is Aramaic and not Iranian

Boyce, Prof Mary/Mani’s spirit and matter/ April 7, 2006

http://www.cais-soas.com/CAIS/Religions/iranian/Manichaeism/manichaeism.htm7. Ginza Rabba /Ginza Rba, the Holy Book of the Mandaeans. - 8. An Inquiry into the Importance and Understanding of the Sabian Mandaeans / (Final Part).

http://www.iranwire.com/print/34/59579. Abdullah Moballegh Abadani /The History of Religions and Sects of the World / Entesharat Mantegh (Sina) / Qom / 1994 / Volume 2 / Page 28.Muhammad ibn Abd al-Karim Shahrastani / Al-Milal wa al-Nihal / Translated by Mohammad Reza Jalali Naini / Entesharat Iqbal / Tehran / Fifth Edition / 2005 / Volume 1 / Page 409.11. Ibn al-Nadim / Al-Fihrist / Translated by Mohammad Reza Tajaddod / Entesharat Asatir / First Edition / Tehran / 2002.

12. Dr. Manijeh Mushiri Tafreshi / Mani and His Religion / Chista Magazine / Tehran / Year 16 / Issues 4 and 5 / Page 327.

13. Mary Boyce, /Iranian Religions: Manichaeism

According to Ibn an-Nadim, Patteg left Hamadan for al-Madain in Babylonia. One day, in a temple which he frequented there, he heard a voice from the sanctuary summoning him to renounce wine, meat, and intercourse with women. Obeying this call, he left al-Madain to join a sect known as the “Mughtasila

http://www.cais-soas.com/CAIS/Religions/iranian/Manichaeism/manichaeism.htm14. Abolghasem Esmailpour Motlagh/The Myth of Creation in Manichaeism/Fekr-e Rouz Publications, First Edition, Tehran, 1996, p. / Page 278.

15. Mani: The Painter Prophet, The Last Prophet? / A Conversation with Professor Touraj Daryaee, Professor of Iranian History at the University of California, Irvine – on the “Ofogh” program from the Voice of America news network about Mani.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NmIR5IzZk4016. This celestial being (angel) is mentioned in Persian texts as “Narjameg”, which is composed of two words: “Nar” (meaning man) and “Jameg” (meaning twin or counterpart)./ The equivalent of this name in Aramaic is Toomā , which Ibn al-Nadīm recorded in al-Fihrist as al-Toom

In Manichaean texts in the Coptic language, this twin is mentioned as saish, which means (pair and counterpart).

“In the surviving Greek Manichaean manuscript, this name appears as suzugos, meaning ‘companion.’ This manuscript, written in Greek, is known as the Greek Mani Codex.”/ “This manuscript was discovered in Egypt, and a summary of it was translated and published in the journal Papyrology in 1970. This treatise is from the words of Mani himself and is, in fact, his autobiography written by his own hand. Baqeri, Dr. Mehri / Tabee’a / Journal of the Faculty of Literature of Tabriz / Issue 166 / pp. 26 and 27.” - 17. Faraqlit: An angel or prophet whom Jesus foretold would come after him. Mani considered himself to be the Faraqlit prophesied by Jesus and the savior of humanity.

Abolghasem Esmailpour Motlagh / The Myth of Creation in Manichaeism / Fekr-e Rouz Publications / First Edition / Tehran, 1996 / p. 275.

And also:

Faraqlit: Meaning “Comforter,” “Intercessor,” and “Bringer of Relief.” Its Greek equivalent is Parakletos (Parakletos):

An Examination of the Meaning and Concept of Faraqlit in Christianity / Tohoor Encyclopedia (Knowledge Base) Website.

http://www.tahoor.com/fa/Article/View/210688

And also:

one who pleads another’s cause with one, an intercessor 1. of Christ in his exaltation at God’s right hand, pleading with God the Father for the pardon of our sins

biblestudytools: http://www.biblestudytools.com/lexicons/greek/nas/parakletos.html - 18. Ibn al-Nadim / Al-Fihrist / Translated by Mohammad Reza Tajaddod / Asatir Publications / First Edition / Tehran / 2002 / p. 583.

And also:

Geo Widengren / Translated by Nezhat Safa Isfahani / Mani and His Teachings / Tehran / Markaz Publishing / 2011 / p. 40.

And also:

Mehdi Bagheri / Religions of Ancient Iran / Tehran / Qatreh Publications / First Edition / 2006 / p. 96. - 19. Maryam Bakhtiyar, / An Analysis of Manichaean Mysticism / Journal of Islamic Mysticism (ʿIrfān-i Islāmī) / Tehran / 2006 / Volume 2 / Issue 8 / pp. 54–55.20. Abolghasem Esmailpour Motlagh / Culture and Myth, “Manichaean Myths” / Anthropology and Culture Website.

http://anthropology.ir/node/28211 - Mircea Eliade / Gnostic and Manichaean Traditions / Translated by Abolghasem Ismailpour / Tehran / Fekr-e Rouz Publications / First Edition / 1994 / p. 137.

- 22. Dr. Abolghasem Ismailpour, / Culture and Myth, “Manichaean Myths” / Anthropology and Culture Website.

http://anthropology.ir/node/2821123. It is astonishing that many Researchers of Mani and Manichaeism have mistakenly claimed that Mani traveled to India during his first journey, which is incorrect. “It is astonishing that many Manichaean scholars have sent Mani to India on his first journey, which is incorrect. Unfortunately, foreign researchers have also repeated their mistakes by referring to these articles and books.

In Iran— in southern Khuzestan—there was a historical city called Hendijan (also referred to as Hendigān), which was sometimes simply called “Hind.” This city still exists in the same location and is one of Iran’s historical and mythological cities. And a water-rich river, called ‘Zohreh,’ flows through it.

http://travel.stad.com/index.php?city_id=131559

Another point is that the Indian subcontinent (India) was known as “Bharat” in the 3rd century AD and was not originally called India.

http://pediaa.com/why-india-is-called-bharat

In addition, all this time for traveling to and from the Indian subcontinent and staying there for two years would not have been sufficient. According to these researchers, Mani traveled to India in the final year of Ardashir’s reign and returned to Ctesiphon at the beginning of Shapur’s reign—that is, in less than a year. So, how could he have spent two or three years in India promoting his religion?

Ahmad Abdolhosseinian / “Identifying Errors in the Historiography of Khuzestan” / Site-e Sokhango

http://sokhango.blogfa.com/post-572.aspx

24. Behbahani, Omid / In Understanding the Manichaean Religion / Bandehesh Publications / Tehran / 2005 / First Edition / p. 12

- Among these temples, one can mention the “Hindu Temple” or “Bot Gooran” in Bandar Abbas, which has its own unique features. In this temple, a depiction of “Krishna,” the flute-playing god of the Hindus, can be seen.

Source: Jamjam News / Hormozgan News

http://hormozgannews.com/Pages/Printable-News-3870.html

- 26. Behbahani, Omid / In Understanding the Manichaean Religion / Bandehesh Publications / Tehran / 2005 / First Edition / p. 12

- Ibn al-Nadim, Muhammad ibn Ishaq / Al-Fihrist / Translated and Edited by Mohammad Reza Tajaddod / Amir Kabir Publications / Tehran / 1987 / pp. 583-584

And also: Christensen, Arthur / Iran during the Sassanid Era / Translated by Rashid Yasmi / Sahel Publications / Tehran / 2003 / Vol. 2 / p. 203

- Prof Mary Boyce:

P68/ Tehran Liege 1975/Leiden/Acta iranica9/A reader in Manichaean Middle Persian and Parthian / - Taqizadeh, Seyyed Hassan / Mani and His Religion (Two Lectures at the Iranology Society – Compiled by Ahmad Afshar Shirazi) / Majlis Printing House / Tehran / 1956 / p.10

And also: Mohebbi, Javad / History of Iranian Civilization / Gutenberg Publications / Tehran / 1957 / p. 222

- Richard Nelson Frye / The History of Ancient Iran / Translated by Masoud Rajabnia / Tehran / Scientific and Cultural Publications / Second Edition / 2003 / p. 481

- Kartir (or Kerdir) was a powerful Zoroastrian priest during the Sassanid era who lived under the reign of seven Sassanid kings. It is believed that Kartir’s actions were not only crucial in the establishment of Iran’s official religion but also highly significant in the country’s domestic politics. Kartir opposed Manichaeism as a heresy.

Source: Wikipedia Encyclopedia32. Mehrdad, Bahar / Asian Religions / Cheshmeh Publications / Tehran / 2011 / Fifth Edition / p. 82 - Mircea, Eliade / Gnostic and Manichaean Religions / Translated by Abolqasem Esmailpour / Tehran / Fekr-e Rouz Publications / First Edition / 1994 / p. 225

And also refer to the original English text:

henning/ mani who were on the point of death - Bahar, Mehrdad / Asian Religions / Publisher: Cheshmeh (2011) / Fifth Edition / p. 82

- Homayoun Hemmati / Seyr-e modam / Hoze Honari / Tehran / 1999 / First Edition / p. 170

- 36. Abū Mansūr Tha’ālibī / History of Tha’ālibī / Translated by Fazaeli / Naghareh Publications / Tehran / 1989 / p. 319

37.Arthur Christensen / Iran during the Sassanid Era / Translated by Rashid Yasemi/ Negah Publications / Tehran / 2010 / Third Edition / p. 207

38.Abu Rayhan Biruni / Āthār al-Bāqiyah / Translated by Akbar Dana-Seresht / Ibn Sina Publications / Tehran / 1973 / First Edition / Volume 1 / p. 270

- Z.Behrooz.(Bita) / Calendar and History in Iran / Publisher: Anjoman-e iranweij/ n.d. / pp. 11 and 113

40.https://fa.wiktionary.org/wiki/%D8%AE%D9%88%D8%B2%D8%B3%D8%AA%D8%A7%D9%86

- Website: Ganjoor / Section 15 / The Reign of Shapur

- Mani in the Image of Iranian Art and Literature/ Jafar Jahangir Mirza Hesabi and Manijeh Kangarani/ Research Journal of Humanities / Issue 58 / Summer 2008 / pp. 23-36

![]()